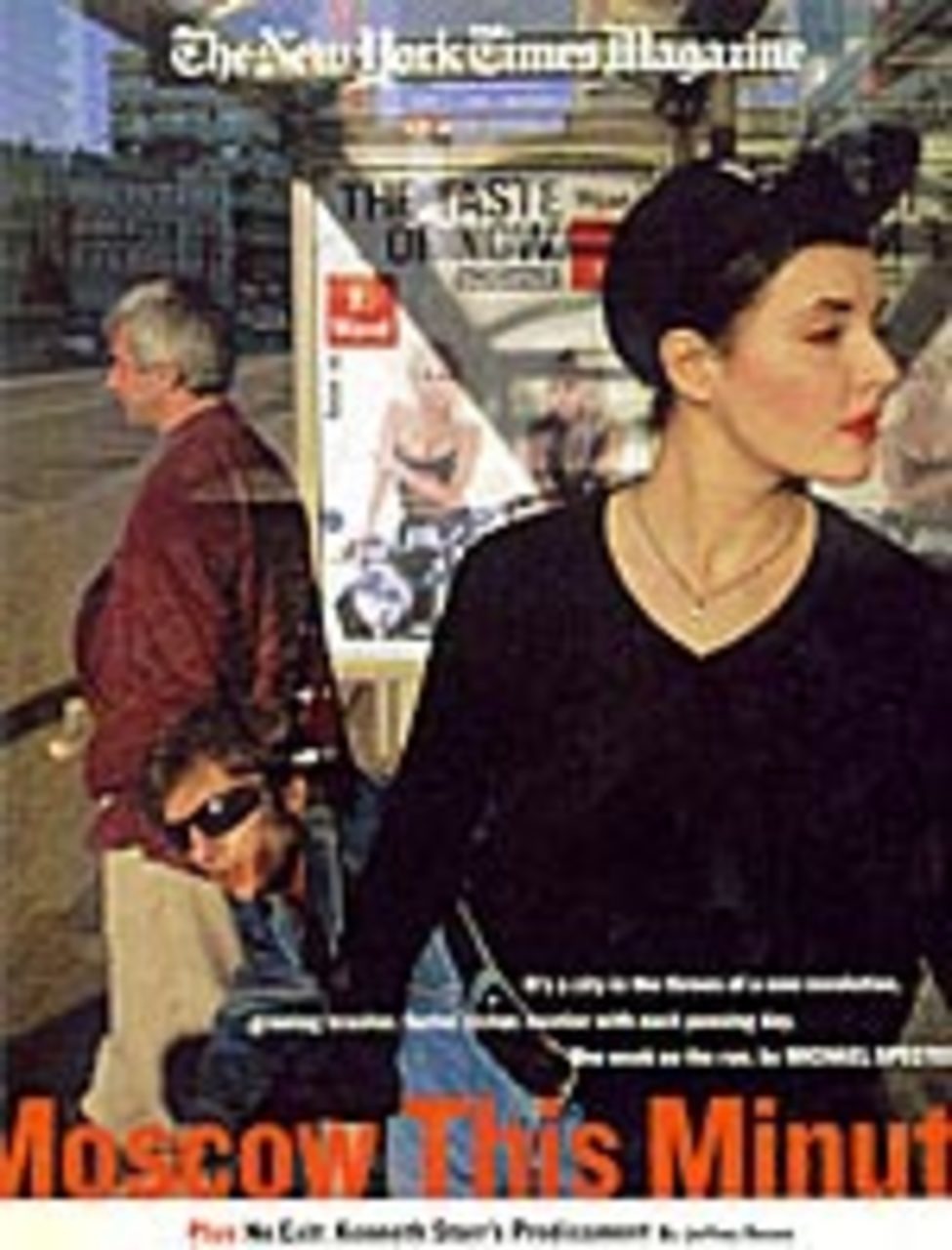

New York Times Magazine , June 1997

It's a city in the throes of a new revolution, growing brasher, faster, richer, nastier with each passing day. One week on the run, by MICHAEL SPECTER.

Monday Dawn, with its shafts of light and hints of redemption, doesn't really happen in Moscow. At some point the black of night dissolves into the gray of day. Long trucks full of beets, cabbage and the first spring melons start rumbling across the broken pavement to their destinations at scores of city markets. People rouse themselves, drink tea, then shuffle across the snowy ground to 500 trolley stops and subway stations... Moscow was once a city of cobblestones, lilacs and church bells. That gave way to vulgar skyscrapers, pompous squares and soulless factories. Now it is a city of astonishing extremes and volcanic activity. The opulence is breathtaking and the poverty is staggering. There is enough neon to rival Reno, but the biggest and most important of the many new buildings under construction is a cathedral. Prostitutes literally line the tawdry streets at midnight, but it has been at least 200 years since faith has been as important or as apparent here.The emerging Moscow - frantic, aggressive, devoted above all to the pursuit of the dollar, is more than the sum of its disparate cliches: it is quite clearly a city of license, of danger and despair. But it is also a center of culture, of yearning, of true possibility. Moscow is so radically different from any other place in Russia that at times the gigantic metropolis seems like a country unto itself. Two-thirds of all the foreign investment in this huge land is centered here. So is most of the cash, crime and corruption. Suddenly, Moscow has become brasher than New York, faster than Tokyo, more clannish than Beirut...

Monday Dawn, with its shafts of light and hints of redemption, doesn't really happen in Moscow. At some point the black of night dissolves into the gray of day. Long trucks full of beets, cabbage and the first spring melons start rumbling across the broken pavement to their destinations at scores of city markets. People rouse themselves, drink tea, then shuffle across the snowy ground to 500 trolley stops and subway stations... Moscow was once a city of cobblestones, lilacs and church bells. That gave way to vulgar skyscrapers, pompous squares and soulless factories. Now it is a city of astonishing extremes and volcanic activity. The opulence is breathtaking and the poverty is staggering. There is enough neon to rival Reno, but the biggest and most important of the many new buildings under construction is a cathedral. Prostitutes literally line the tawdry streets at midnight, but it has been at least 200 years since faith has been as important or as apparent here.The emerging Moscow - frantic, aggressive, devoted above all to the pursuit of the dollar, is more than the sum of its disparate cliches: it is quite clearly a city of license, of danger and despair. But it is also a center of culture, of yearning, of true possibility. Moscow is so radically different from any other place in Russia that at times the gigantic metropolis seems like a country unto itself. Two-thirds of all the foreign investment in this huge land is centered here. So is most of the cash, crime and corruption. Suddenly, Moscow has become brasher than New York, faster than Tokyo, more clannish than Beirut...

MASHA TARASEVICH FINDS HERSELF having been treated strangely - and not unkindly - by fate. A savvy brunette with killer legs and a beeper that never stops, the Masha hit the big number last year when she became the first centerfold for the Russian edition of Playboy. In a competitive city filled with the world's most beautiful and available women they are commonly called dostupniye dyevochki, "accessible young ladies" - Masha became the "it" girl overnight.

She didn't plan to make history; it just sort of fell to her. Not usually a Playboy reader, she bought a copy to read an interview with Cindy Crawford. "She is my ideal," Masha says in her best Dale Carnegie voice. "Sensual, smart, successful."

"I saw the ad for the first Russian centerfold and I thought I would win," she continues matter-of-factly, weaving her cherry red Lada through the horrendous midday traffic and listening intently to "Erotica" by Madonna on the tape player. ("Oh, God, I respect her so much," she says.) "I got scared about Playboy for a while," she recalls. "I wondered if it would define me. I asked my boyfriend and he told me I just have to respect myself. And I do." So Masha, shown in various stages of undress in, among other places, a subway stop (Revolution Square), a snowdrift and a bathhouse, quickly earned herself a special niche in New Russian history. ("I think of them as art," she says, mouthing the official line of centerfolds the world over. "These pictures are about feminine beauty".)

A budding singer who studied "rock music" at college in her hometown of Minsk, she is riding her centerfold fame as far as it will take her. Masha has already been to Los Angeles to see "the mansion" and to meet "Hef." She plays violin (as anybody who has seen her naked photos in Playboy will surely remember), and her first music video is called "Maestro Paganini."

Masha, who prefers to be called Maitri, her spiritually inspired, "Buddhist" stage name, is looking severe but cool this afternoon in arty black glasses, blue jeans and cowboy boots. Her lipstick is too red and there is too much of it, but nobody who sees her is going to complain.

When she shows up at the Playboy office to ask them to help promote her music, the guard practically starts to salivate. "Do you have any of those pictures on you?" he asks. Masha blinks, tugs at her gold hoop earrings and blows by him as if he's made of stone. "Moscow is the greatest city in the world," she says, flattered by his attention. "It's like that old Frank Sinatra song: 'If you can make it here, you'll make it anywhere.' Isn't that how It goes?"...

MASHA IS RELAXING AT HOME TONIGHT. SHE shares a large, wood-paneled apartment with her 22-year-old sister, Vera, and together they pay $1,000 a month in rent. It's a huge sum for two young Russian women, but Vera has jettisoned her plans for a career as a philologist and now runs a successful chemical-equipment company. Masha is having friends over, so she bought a chocolate ice-cream cake, which she eats with abandon. "I can't help it," she says. sharing a small seat with Vera, who abstains. "I love this stuff." This is a bachelorette pad. One friend, Andrei Chernov, is talking about how his car was stolen by an old acquaintance. He is glad. "These days if you have a car in Moscow," he says. "You can die for it."

The phone rings every three minutes. At 10 P.M.: "Nope, that's Easter. Everyone is going to be waiting for me at home. My parents, my grandma everyone." Somebody wants her to be the host of a fashion show in Siberia. "Can't do it." Five minutes later: "Mamutchka. Papa was here yesterday? Doesn't he have my beeper? O.K., maybe next time. I love you."

The talk turns to astrology, pseudonyms, money, men. The phone keeps ringing. "Yes, come over. Come over any time." By midnight the party has just begun...